Parables are stories told to help us see in a new way, to help us get at mysteries that defy simple explanations. In Godly Play, we describe them as gold boxes with lids that we reopen again, each time finding a new way into God’s deep, endless and unfathomable gifts. Jesus’ parables are treasures of our faith tradition, but others tell them as well. One of my favorites is a Zen Buddhist parable about two monks walking down a road. This version is from the beautiful Caldecott honor picture book Zen Shorts by John Muth.

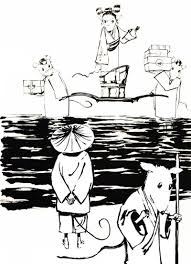

Two traveling monks reached a town where there was a young woman waiting to step out of her sedan chair. The rains had made deep puddles and she couldn’t step across without spoiling her silken robes. She stood there, looking very cross and impatient. She was scolding her attendants. They had nowhere to place the packages they held for her, so they couldn’t help her across the puddle.

The younger monk noticed the woman, said nothing and walked by. The older monk quickly picked her up and put her on his back, transported her across the water, and put her down on the other side. She didn’t thank the older monk, she just shoved him out of the way and departed.

As they continued on their way, the young monk was brooding and preoccupied. After several hours, unable to hold his silence, he spoke out. “That woman back there was very selfish and rude, but you picked her up on your back and carried her! Then she didn’t even thank you!”

“I set the woman down hours ago,” the older monk replied. “Why are you still carrying her?”

This week, as I read through the lectionary readings, those two monks and that arrogant woman kept popping into my mind, making me re-see and rethink some familiar and difficult biblical texts, just as I think God and Jesus might be trying to push Abram and Peter in those passages to new ways of thinking and seeing.

In the Genesis story, God promises Abram and Sarai that they will give rise to nations. This is the story we saw unfold this summer in Godly Play. These are the same words God said to Abram and Sarai at the very beginning of their journeys; they are the original blessing and promise that sent them on their way. Since then, they’ve traveled from Ur to Haran to Egypt and back again, and throughout all of those years, Sarai remained childless. Like the younger monk in the Zen parable, Sarai’s head is now filled with bitterness and fear over the injustice of the situation. Finally, she decides to take matters into their own hands; Sarai gave her slave Hagar to Abram to beget a child through her slave. You’ll all remember what a mess that created! It is right after that piece of the narrative that this passage begins.

What’s most striking here is what God doesn’t say. He doesn’t get angry because they lost faith in his promise and tried their own fix. He doesn’t point out how they’ve made things worse for both Sarai and Hagar. True to the promise he made to Noah, he also doesn’t go back on his covenant. Instead, he repeats it: Abram, you will be the parent of nations, and so will Sarai. And then, strangely and without explanation, he gives two people in their late 90s new names–and with those names, new identities, new futures, new ways of seeing.

I wonder if it’s the realization of what chaos he’s created by not trusting in the covenant that makes Abram fall on his face before the Lord in this passage. What we know is that he rises with a new name, a new hope, and soon the birth of a new son. And God blesses it all, creating nations of kings from both sons, the son born from their doubts, anger, and fear and the son of their new identity.

This week’s Gospel opens with Peter– like the younger monk, feeling all the injustices of power, which he expects his teacher, the one he has just named the Messiah, to correct. Jesus rebukes this thought though far less gently than the older monk. Their point is the same, though: full of righteous indignation, the younger monk and Peter are losing their way . Jesus sees the injustices around him and his disciples just as clearly as Peter does–he spends all his time healing those most hurt by it, fearlessly calling out the authorities. But God’s way is not to seize human power. Like the way of the elder month, who picks up the woman so full of the arrogance that comes with wealth and power–God’s way is to pick up the cross, that terrible and shameful instrument of torture used by the Roman rulers to keep conquered people in check. Jesus carries the cross for and with all of God’s beloved who suffer under its weight. And then, echoing and fulfilling the ancient covenants, his death death mysteriously and wonderfully transforms that pain into a symbol of rebirth and new life.

The final twist in today’s lectionary comes from the psalm. On the surface, this excerpt from Psalm 22 is a straightforward reminder that Gold listens to the poor and to everyone who cries out to him. But that simple, comforting message comes right at the end of the psalm that we know best because we recite it solemnly on Good Friday. It is the psalm that begins, “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?”: the words that Jesus–the Messiah, the elder monk, the steady follower of God’s way–says on the cross. And so Jesus joins our own angry, frustrated, abandoned younger monk voices even in anguished lament.

And so also, back and forth we go, with Abram and Sarai, with Peter and the psalmist, ricocheting from older monk to younger monk: one day, gladly following the One who loves and cares for us; the next, succumbing to those angry voices in our heads too frustrated to see the way forward. And every day, through the promises of the Covenant, through Jesus, who enters so deeply into solidarity with all of who we are, God takes it all, loves it all, transforms it all into blessing and new life.

Powerful words…..thank you

LikeLike